Sovereign Wealth and Petro-State Capitalism: Diversification, Not Dislocation

Economic Transition Takes More Than a Generation, and Diversification Demands More Than Capital

Strategic Development Funds: Building Beyond the Barrel

In the Arabian Gulf, Strategic Development Funds are tasked with a singular challenge: to diversify economies away from oil. This mandate is not merely fiscal—it is existential. Petro-state capitalism, long anchored in hydrocarbon rents, now seeks to manufacture competitive advantage in other sectors. The formula is familiar: subsidised capital, cheap energy, abundant labour, and strategic geography. Temasek in Singapore, Mubadala in Abu Dhabi, and the Investment Corporation of Dubai have demonstrated that, with time and institutional discipline, mid-sized economies can evolve beyond resource dependence. Their success has inspired replication—but rarely duplication. Diversification is a slow burn, and city-states with technocratic policy-makers have been more successful than (geographically and economically) larger petro-economies.

These funds operate at the intersection of economic policy-making and global capital markets. Their success depends not only on asset allocation, but on institutional credibility, regulatory clarity, and the ability to onshore private co-investment. In many cases, they serve as both investor and market-maker—catalyzing sectors that anchor their competitive advantage (think Dubai or Singapore) or strategically invest in sectors that pave their influence in our current state of geo-economics. One challenge remains: how to transition from oil-driven GDP to a dynamic economic model that diversifies away from hydrocarbons.

Saudi’s Super Fund: Vision, Velocity, and the Soft Budget Constraint

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) was established to lead the charge under Vision 2030—a bold reimagining of the Kingdom’s economic future. Petro-state capitalism, in its most ambitious form, was deployed across sectors from tourism to tech, anchored by giga-projects designed to reshape infrastructure and global perception. The listing of oil giant Aramco provided liquidity and structurally high oil prices enabled a soft budget constraint—a fiscal environment where spending outpaces revenue. Buffered by sovereign reserves, it was a bet on transformation, underwritten by hydrocarbons.

The giga-projects—NEOM, The Line, Red Sea Global—were not just infrastructure plays; they were narrative instruments. Designed to signal a new Saudi Arabia to global investors, they aimed to reposition the Kingdom as a hub of innovation, sustainability, and openness. By now, it is clear to most that the scale of ambition came with fiscal implications. In economic terms, the soft budget constraint refers to a situation where state-backed firms can survive through a sustained period of losses due to the financial aid of a paternalistic state (Kornai). The soft constraint, while enabling rapid deployment, also masked underlying fragilities—particularly the reliance on oil-linked liquidity to sustain non-oil growth.

The Return of the Hard Budget Constraint

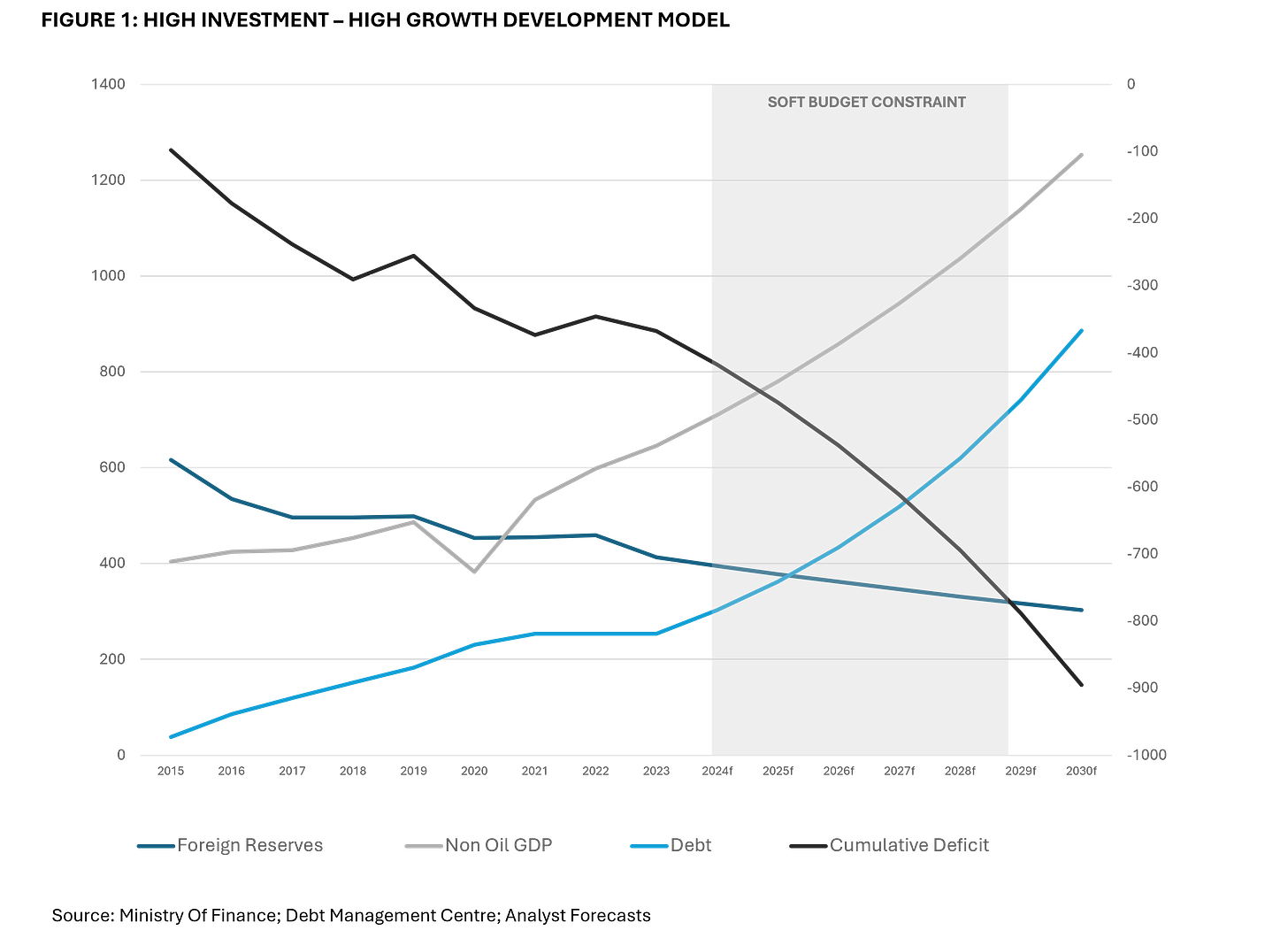

In early 2024, I argued that Saudi would need to re-enter a hard budget constraint. Non-oil GDP was expanding, but so was debt—and oil revenues were no longer sufficient to sustain the scale of giga-project ambitions. The increasing footprint of the state in domestic markets raised concerns among foreign investors, wary of competing with PIF’s capital and mandate. It is a paradox: the very instrument designed to attract investment can, if overextended, deter it. From late 2025 through 2027, a recalibration is inevitable. Figure 1 outlines the fiscal inflection point I predicted in 2024.

This shift is not a retreat, but a recognition of economic gravity. As the state assumes a larger role in shaping market outcomes, the need for fiscal discipline becomes more acute. The transition from soft to hard budget constraint is not a failure of Vision 2030—it is a maturation of its implementation. It reflects the reality that diversification, to be durable, must be financially sustainable.

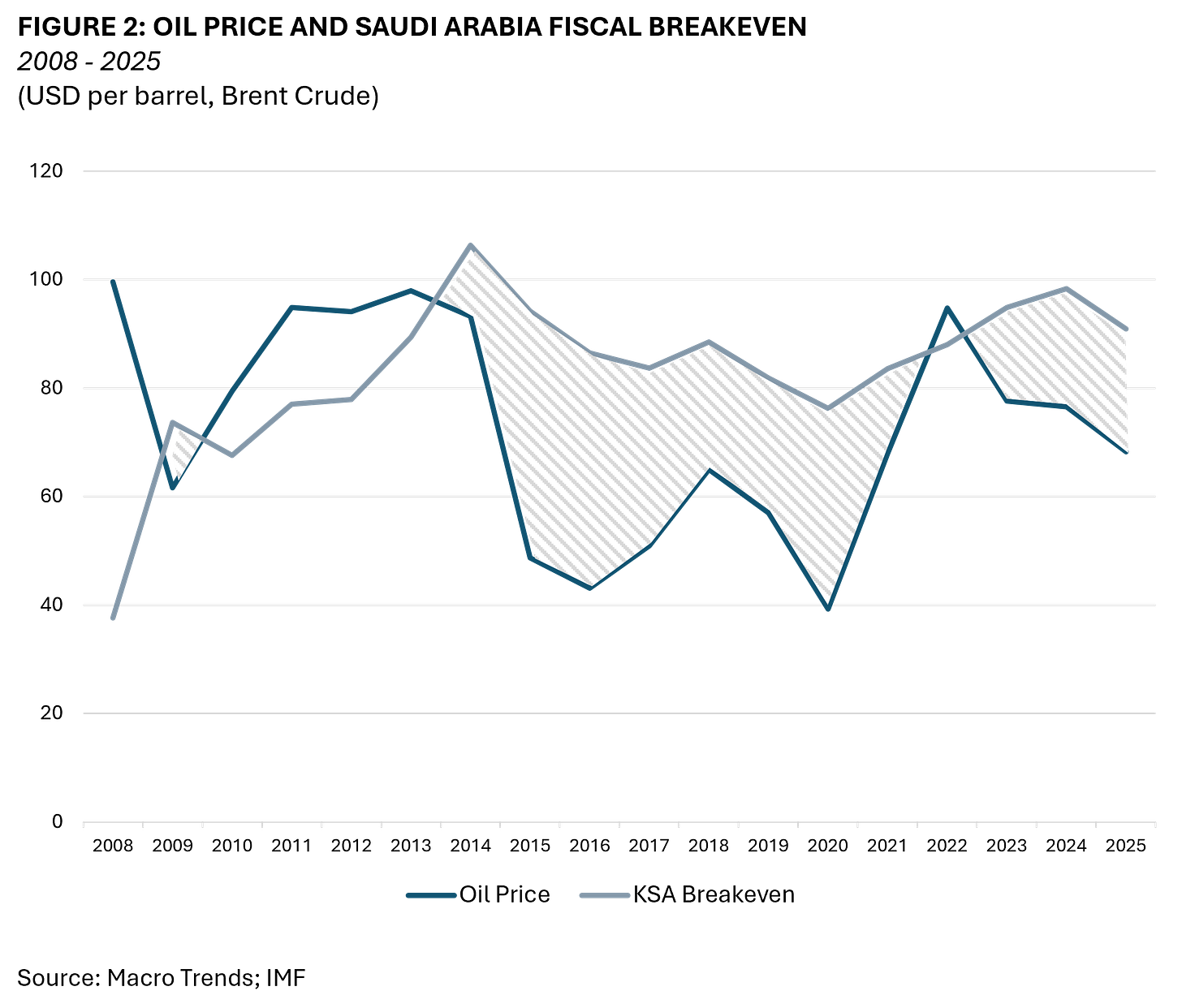

Impairment, Not Retreat: The Long Road to Transition

PIF’s 2024 annual report confirmed the first write-down in its giga-project portfolio ($8 Bn) —an impairment that signals fiscal realism, not strategic retreat. The ambition remains, but the path is steep. PIF has returned to debt markets, issuing $2 billion in dollar bonds to finance its investment plans amid an oil price shock. Liquidity, not solvency, is the constraint. Debt-to-GDP remains healthy, but the scale of infrastructure, a new airline, and urban development—alongside preparations for Expo and the World Cup—requires sustained capital flows. Petro-state capitalism thrives in times of surpluses – but regional challenges and domestic demographic pressures alongside ambitious development goals has moved fiscal breakeven to barrel higher. Figure 2 highlights that since the launch of Vision 2030, the Kingdom has sustained a prolonged period of fiscal deficits in pursuit of its development agenda. It underscores the reality that economic transformation is not linear, and that setbacks are part of the process. Diversification demands patience, and patience demands liquidity.

Asset Transfers and the Petro-Dollar Paradox

In 2024, PIF’s AUM grew significantly, driven by the transfer of Aramco shares. The rationale was clear: bolster the asset base, improve credit ratings, and unlock debt capacity. But the paradox is unavoidable. While the long-term vision is to decouple from oil, the short-term mechanism remains petro-dollar dependent. PIF’s portfolio is increasingly strategic, but only 8% is allocated internationally. It resembles a Development Fund more than a Stabilisation Fund—focused on domestic transformation rather than global hedging. Transparency is commendable, but the balance sheet tells a story of transition, not completion.

This transfer also reflects a broader trend in petro-state capitalism: the recycling of oil wealth into state-led diversification vehicles. It is a form of internal monetisation, where sovereign assets are reshuffled to create fiscal space. The risk is that it also reinforces the structural reliance on hydrocarbons, even as the narrative shifts toward post-oil futures.

2025: A Year of Reckoning

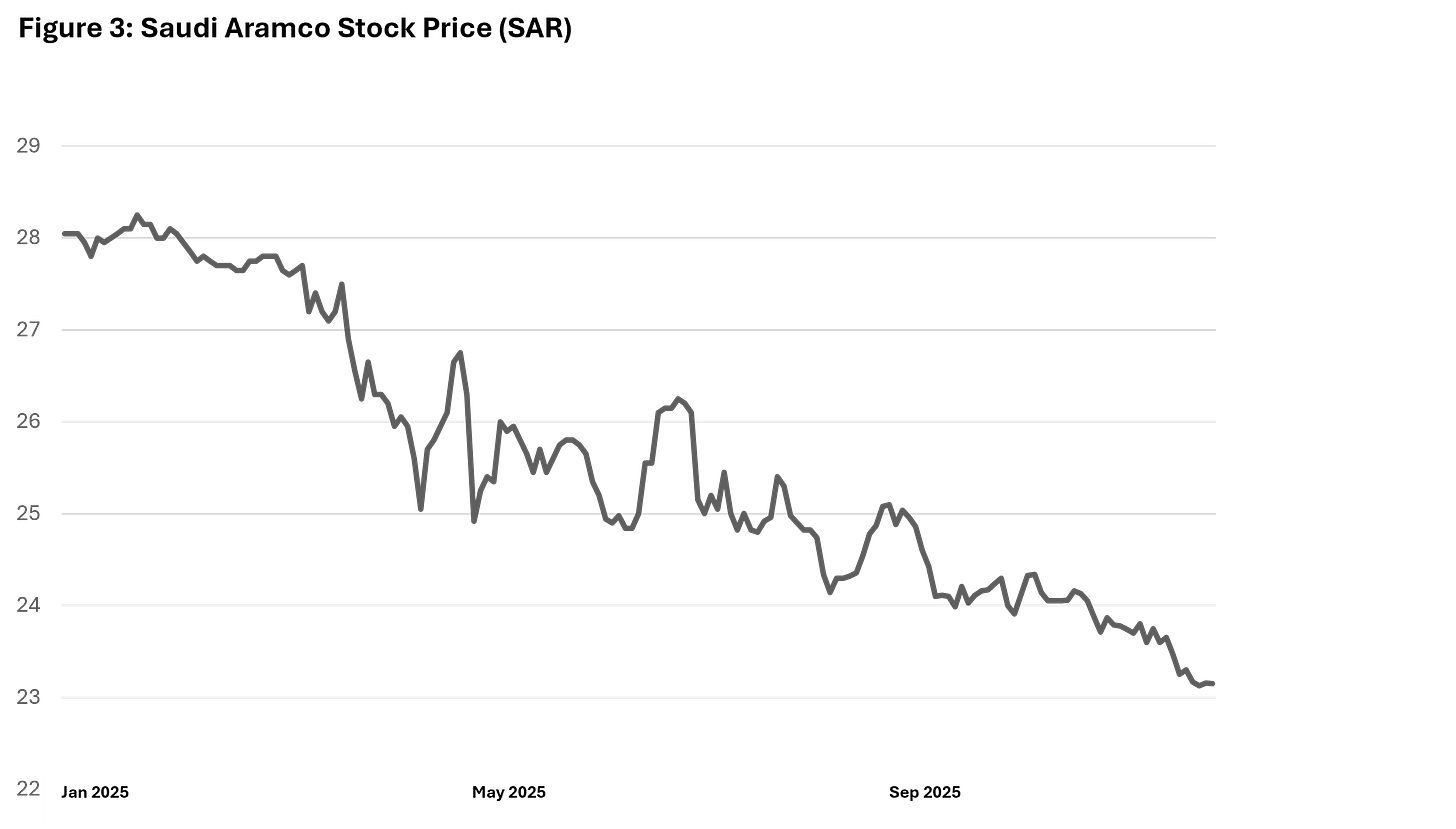

The year ahead will test PIF’s resilience. Aramco’s share price has underperformed, and the energy sector faces headwinds. Year-to-date it is down 17.5%. According to the IEA, global demand remains subdued despite geopolitical tensions. A conservative outlook on oil prices will constrain liquidity, slowing the pace of Saudi’s growth agenda. Vision 2030 remains a strategic imperative, and Saudi’s scale and demographics ensure eventual transformation. But the timeline is stretching. The next five years will be defined not by acceleration, but by adjustment.

Investor sentiment is shifting. The initial euphoria around giga-projects is giving way to questions about execution, returns, and governance. PIF must now navigate a more sceptical market, balancing ambition with accountability. The challenge is not whether Saudi can diversify—but at what cost.

Saudi will remain and rely on its oil economy for this lifetime and its development agenda cannot be counter-cyclical to oil prices. The industrial revolution took a century, Singapore is 60 years into its journey; the UAE 50. Petro-states seeking structural shifts in their economic models will need to adjust their timelines with a hard budget constraint. The path forward is clear: it is long term economic diversification, not dislocation.